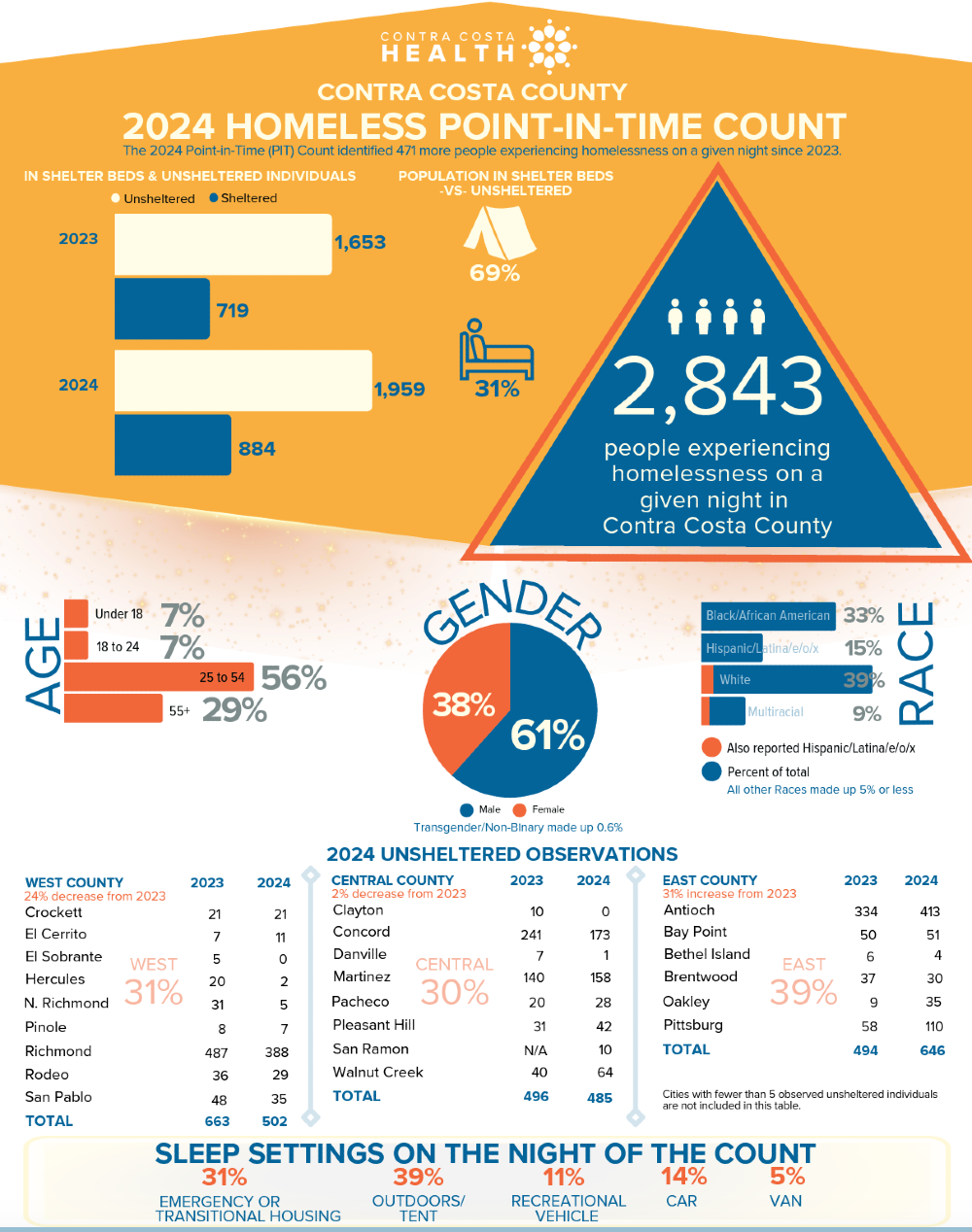

Richmond’s homeless population decreased by 20 percent, according to new information from the 2024 Contra Costa Health Services Point-in-Time Count. Homeless services provider Safe Organized Spaces says the actual numbers are considerably higher.

The annual survey documents people experiencing homelessness and provides a one-day snapshot of homelessness in Contra Costa. The county’s homeless services team and more than 200 volunteers spread out across the county to count the number of people living outdoors or in emergency shelters on January 25.

The survey is conducted by local organizations on behalf of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to assess the number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States. HUD uses the information gathered during the counts to assess the effectiveness of local agencies in alleviating homelessness and to determine the amount of funding they require.

In Richmond, 388 people without housing were observed during this year’s count, down from 487 the year before, a number SOS’s Director of Programs and Wellness O’Neill Fernandez says is “absolutely false.”

Grandview IndependentSoren Hemmila

Grandview IndependentSoren Hemmila

According to the point-in-time count, the entire West County saw a 24 percent decrease in homelessness compared to 2023. North Richmond has dropped to five people, zero in El Sobrante and 35 in San Pablo.

“I don’t know if I can say that there is an increase but definitely not a 24 percent decrease,” Fernandez said. “Just in San Pablo alone, I can think of one encampment with the numbers they had for the whole of San Pablo.”

Fernandez and members of SOS were a part of the PIT and counted the highest number of individuals in West County. SOS and the Coordinated Outreach Referral, Engagement (CORE) program were the only teams allowed to leave their cars during the count.

“That is because we know where to go, and we could get out of the car and say yes, there is a whole encampment down there where no one else could,” Fernandez said. “Every one of my team members had lived in an encampment.”

Fernandez said the county could learn from other successful approaches like Alameda’s. Alameda’s strategy incorporates the personal experiences of individuals into their point-in-time count, which helps collect accurate numbers.

Contra Costa County District 2 Supervisor Candace Andersen said the point-in-time count is a tool that provides a rough estimate of community needs on any given day and is not a true census of the unhoused population.

“Some cities that sustained or strengthened efforts to address homelessness, particularly outreach, showed significant improvement,” Andersen wrote. “Richmond (-99) used an $8.6 million state grant to transition nearly 100 residents of a large encampment into housing.”

Grandview IndependentSoren Hemmila

Grandview IndependentSoren Hemmila

Safe Organized Spaces Executive Director Daniel Barth says the county point-in-time count is only a three to four-hour process conducted at 5 a.m. on a cold, wet January morning and is built for failure.

“The reason they do it for 3-4 hours in the morning is they don’t want to double count people. So they want to eliminate duplication, but it is at the expense of not counting people at all,” Barth said. “There is a structural ineffectiveness that is built into this count process.”

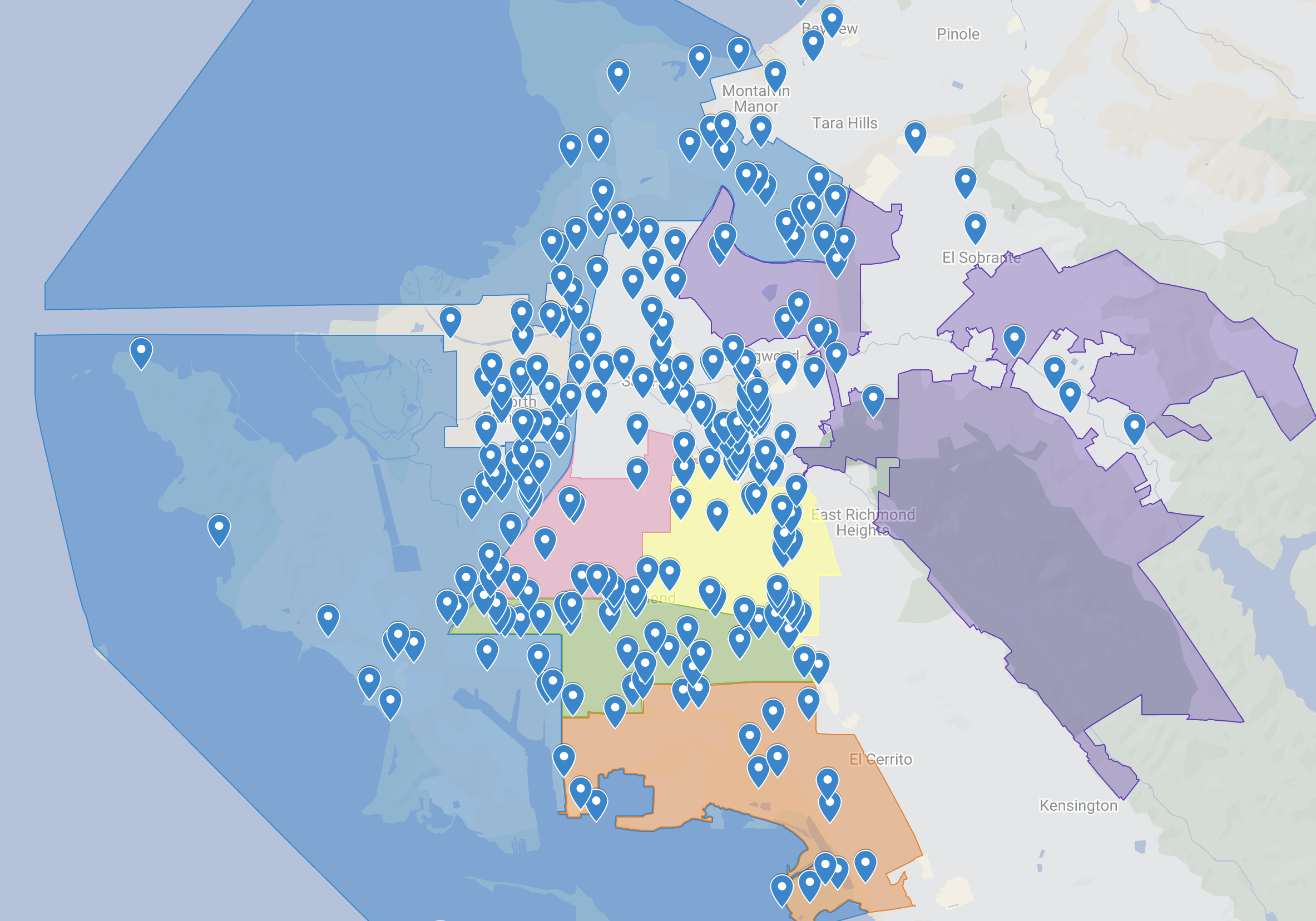

A month before the county PIT, SOS utilized an unhoused SOS employee with extensive experience and relationships with unsheltered people to map homeless encampments.

“There is one person in particular that knows more than anyone else who is in the communities and where to go,” Barth said. “That doesn’t make any sense to an institution like the county. But it makes total sense when you are thinking about someone who knows the neighborhood and the community.”

1,715 unhoused individuals in Richmond

SOS counted 1,715 unhoused individuals in 196 hotspots in the greater Richmond region and 564 unhoused people in San Pablo at 56 locations.

“Our belief is you need to know someone to actually support that person,” Barth said. “If you don’t know an encampment exists that is why we have the problem that we have.”

SOS uses its count of un-household people to locate individuals in need of support and bring resources to them. Barth says the point-in-time count is misconstrued as something useful when it really isn’t.

The population counts are used to gather demographic data, but Barth said the PIT count does not accurately capture a population's makeup by capturing the most visible homeless people who have the least amount of resources to address their situation.

“It is not a representative sample because you are only counting people on the street,” Barth said. "They are the most symptomatic with mental illness or other conditions that lead them to being right on the street,” Barth said.

Barth said one example of these encampments is the large undocumented population in the creeks of North Richmond and San Pablo. Barth explained that they live in the creeks to remain as hidden away as possible.

Some unsheltered people living far off the beaten path may have never encountered CORE representatives. CORE is usually contacted when the police are involved or complaints generate an abatement or removal of an encampment. Trying to get someone into a shelter does not work when they are being removed from their encampment.

“Whereas if you work with someone over time, you can help them get into housing,” Barth said.

Click to become a Grandview Supporter here. Grandview is an independent, journalist-run publication exclusively covering Richmond, CA. Every cent we make funds reporting from Richmond's neighborhoods. Copyright © 2024 Grandview Independent, all rights reserved.